Folk musician Charlie Marks discusses his winding path to a fulfilling life of music and nature. After an aimless period post-college, some breakdowns, and living out of his car, Charlie found his way through small steps like open mics and odd jobs. Learning the clawhammer banjo clicked for him, and he's since released several albums. Now living a rural life in Reno, Nevada, Charlie reflects on using music as self-expression and finding inspiration in old folk songs.

---

Guest info:

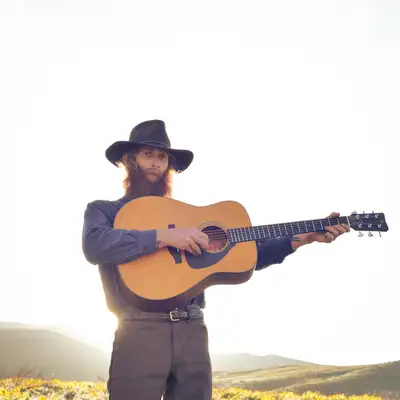

Charlie Marks

Charlie Marks is a banjo & guitar picking folk singer from outside Reno, Nevada. Charlie blends together traditional and original folk tunes to weave together heartfelt stories. Charlie is also a poet and writer and aspiring chicken farmer.

Website - https://charliemarksmusic.com

Instagram - https://instagram.com/charlie_marks_music

---

Want more of the show? Check out all of our links below:

Website - https://www.unfilteredunion.com

Get full access to Unfiltered Union at unfilteredunion.com/subscribe